In four years as a search marketer, I built - in collaboration with my team of analysts and our partners in data science, ad tech, and storefront - $87 million of annualized, incremental revenue for Wayfair. Molto bene! Here are three frameworks that I used to pick bets and execute them quickly.

1. Define what’s important and what’s not

From a single 90 minute focus session to a 2-year roadmap, knowing what to focus on makes it so much more likely that by the quarterly performance slide, you’ll have achieved some substantial, measureable results to write in. And it’ll even let you manage upwards, telling your boss “I can get that done, but I think we should focus on A and B first, for reason X”.

My key insight here is that different prioritization techniques work best for different time horizons. Here are explanations of the 3 techniques I’ll be discussing, courtesy of ChatGPT:

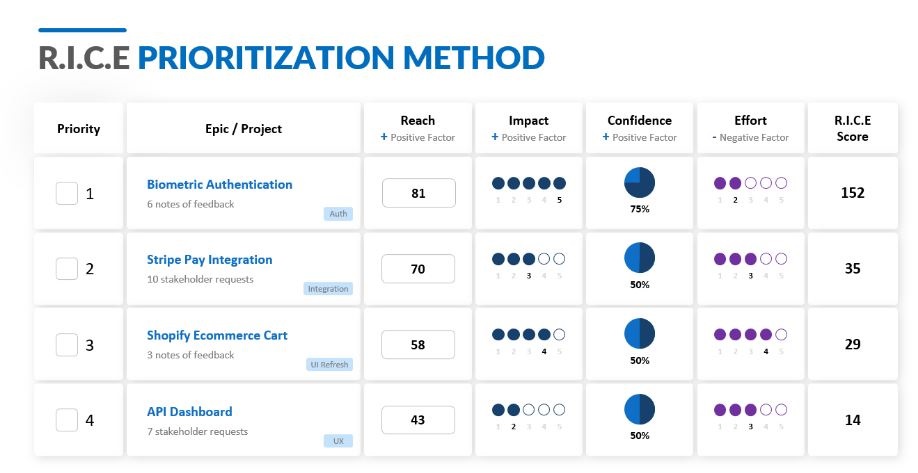

RICE prioritization

The RICE prioritization framework is a popular tool used by many product managers and project managers. It stands for Risk, Impact, Confidence, and Effort, and it is used to prioritize tasks or projects based on four key factors.

- Risk: This factor measures the potential risks associated with the task or project. For example, a project that involves developing a new product has a higher risk than a project that involves minor improvements to an existing product.

- Impact: This factor measures the potential impact of the task or project. For example, a project that has the potential to significantly increase revenue has a higher impact than a project that has a minor impact on revenue.

- Confidence: This factor measures the level of confidence that the team has in the task or project. For example, a project that has a well-defined plan and clear objectives has a higher confidence level than a project that lacks clarity and structure.

- Effort: This factor measures the amount of effort required to complete the task or project. For example, a project that requires a significant amount of time and resources has a higher effort level than a project that requires minimal effort.

To use the RICE prioritization framework, assign a score to each of these four factors, and then multiply them together to get a final score. For example, if a project has a risk score of 8, an impact score of 7, a confidence score of 9, and an effort score of 5, its RICE score would be 2520 (8 x 7 x 9 x 5). (Editor’s note: curiously, ChatGPT got the RICE equation wrong. This is a program that can beat stockfish, the world’s best chess-playing algorithm! While you multiply RIC together, you then divide by effort, since higher effort equals more bad. So that project described would have a RICE score of 101 (8 x 7 x 9 / 5)).

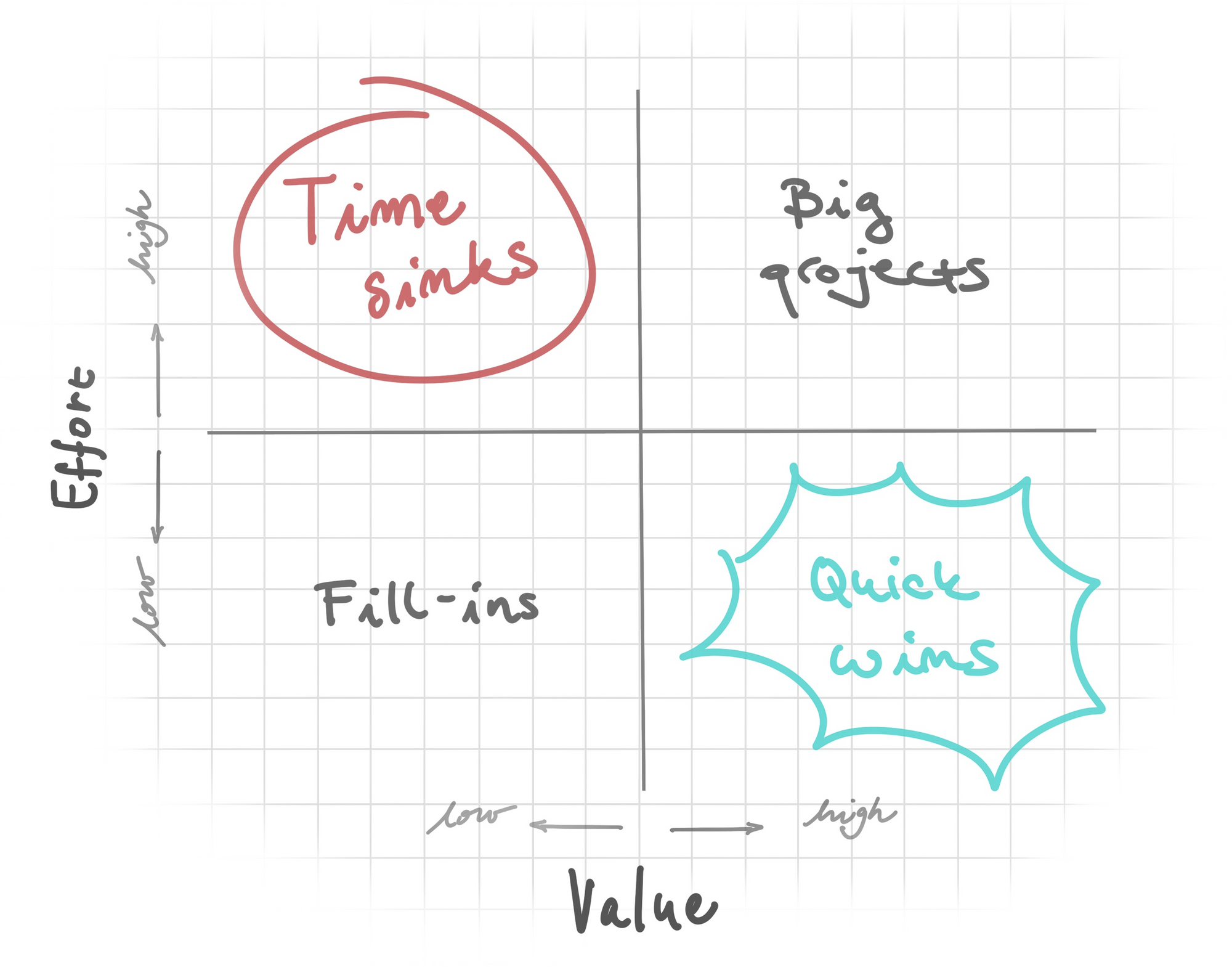

Effort vs. Value

The effort vs. value framework is a simple and effective way to prioritize tasks or projects based on their potential value and the effort required to complete them.

- Effort: This factor measures the amount of effort required to complete the task or project. For example, a project that requires a significant amount of time and resources has a higher effort level than a project that requires minimal effort.

- Value: This factor measures the potential value of the task or project. For example, a project that has the potential to significantly increase revenue has a higher value than a project that has a minor impact on revenue.

To use the effort vs. value framework, plot each task or project on a graph with effort on the x-axis and value on the y-axis. Tasks or projects that require high effort but have low value should be deprioritized, while tasks or projects that have high value and low effort should be prioritized.

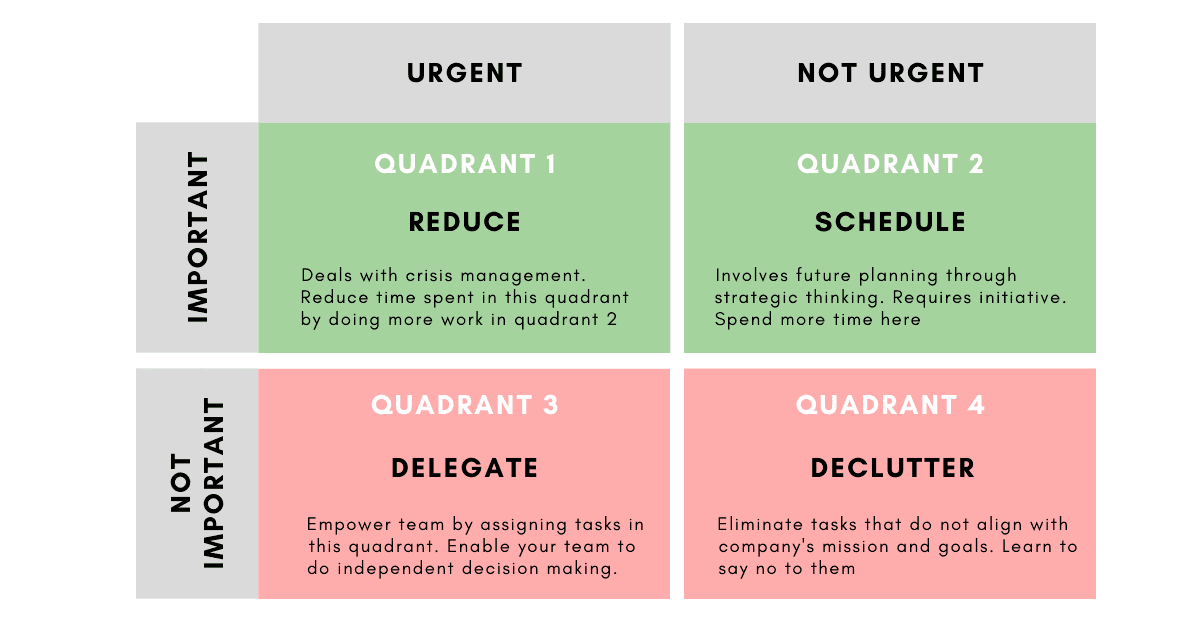

Urgency vs. Importance

The urgency vs. importance framework is a classic tool used to prioritize tasks or projects based on their urgency and importance.

- Urgency: This factor measures how quickly the task or project needs to be completed. For example, a task that has a tight deadline has a higher urgency than a task with a more relaxed deadline.

- Importance: This factor measures the importance of the task or project. For example, a task that is critical to the success of a project has a higher importance than a task that is not critical.

To use the urgency vs. importance framework, plot each task or project on a matrix with urgency on the x-axis and importance on the y-axis. Tasks or projects that are both urgent and important should be prioritized, while tasks or projects that are not urgent or important should be deprioritized.

Putting it all together

To determine what to do for the next 6-12 months, I’d start with a brainstorming session, getting all of the ideas from the team on paper, without judging their quality. Then, I’d quickly sort ideas on a 2x2 matrix of effort and value. There’s probably a lot of ideas, and I want to pluck the low hanging fruit - those high value, low effort ideas - as quickly as possible.

Once I have a set of “viable” ideas from the effort vs. value exercise, I’d run them through full RICE prioritization to figure out the relative quality of each, which I’d use to construct my roadmap. RICE is the most thorough of the prioritization schemes, and works well when you have time to cross-compare everything and determine the best possible rank order.

To determine what to do right now - today, or in my next 90-minute focus session - I’d look at my candidate projects’ urgency vs. importance (aka the Eisenhower matrix). Highly urgent AND highly urgent? You’d better finish this prioritization exercise quickly because that work won’t do itself. Not important? Why is it on your list? Can it be eliminated, reduced, or snoozed? This 2x2 matrix works best for short-term projects since it takes into account how project timelines compete against each other; for example, if a team is relying on your piece of the project to stay unblocked, it could be more urgent and important to finish it before working on an easier, higher value project. And it’s helpful to sequence this after RICE, since your key initiatives’ RICE scores are typically the biggest input into a project’s “importance”.

As an aside, I sometimes find it’s hard to quickly say no to things with at least some value, especially if there’s a stakeholder on the other side. For this reason I also keep a bucket on my to do list of “probably never doing”. This lets me demarcate that I probably will never have time to prioritize something, without my to-do list falling prey to the endowment effect. I can also keep it top of mind for a bit while I process whether it’s really worth taking off the list. Just note that if something goes on the “probably never doing” list, it’s usually smart to proactively get alignment with stakeholders!

2. Manage your analysts to their skill level

Synopsis: give analysts work that’s easy enough for them to achieve on time, but hard enough to force them to grow, with just enough support that they’re never stuck for too long.

Foundational to succeeding as a manager is being able to “scope” large, ambiguous problems: clarifying their outputs, and breaking down the steps to get there into more concrete pieces. An example problem statement could be: “every customer who clicks on a product listing ad gets sent to the same landing page template. How do we change the landing page to create more revenue”? You can’t just give that problem to a day 1 new hire out of school (i.e. a level 1 or L1): chances are, they’ll spend a long time on it, and perhaps produce a recommendation, but with weak evidence that it’s the highest value and lowest effort option possible.

Instead you need to define the goal (grow revenue, or save costs and reinvest them), and create a project structure, such as this:

- Create a MECE framework for what drives value on the page based on the different components of the page.

- As the first layer, consider the different components of the page: the advertised product image, its details and option selection, the add to cart button, the recommendations grid, the browse filters, the additional products carousel, and the page footer.

- As the second layer, consider how the components are created (e.g. for the recommendations grid, which products are eligible to be featured? How are they ordered? How is their size determined? Which details get featured for each product?)

- Size the usage of each of these components (clicks, mouse-overs, and views) to determine where to focus our analysis

- Analyze each of those components to identify trends and generate hypotheses for how we could hit our goal by changing the components

- Launch an MVP test to confirm one of the hypotheses

- If successful, scale it across e.g. product classes, geographies, brands, etc.

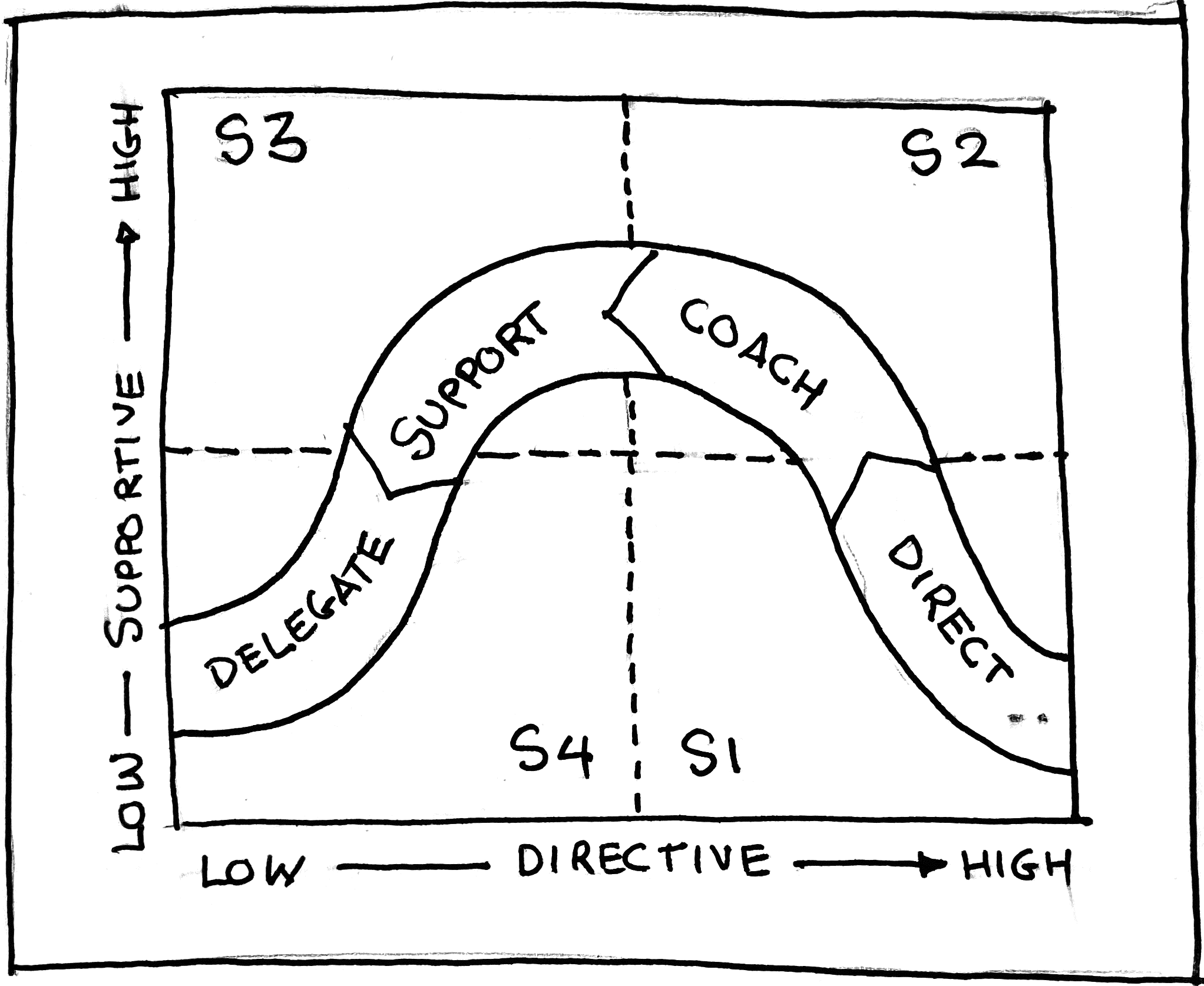

Then assess: is it scoped enough for an analyst to run? Maybe: each of these steps still has a lot of ambiguity, especially 1 & 3. A strong senior analyst could succeed here, with the right coach. And that brings us to the Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership model. Situational leadership is a powerful tool to get the most out of your analysts without overly micro- or macromanaging. In a nutshell, it’s giving employees just enough support so that they can make their own decisions of whatever complexity level they can handle. Take it away, chatbot:

Situational leadership is a management style that recognizes and responds to the needs of different employees in different situations. It is a flexible approach that can be used to motivate, empower, and challenge employees to reach their goals. Based on the needs of each individual or team for a given task, situational leadership calls for one of four approaches:

- Directing is most appropriate when an employee is new to a task or organization. It involves the leader providing clear instructions and expectations and closely monitoring performance. The leader should outline step-by-step what they want the employee to do and provide guidance as needed.

- Coaching is an appropriate strategy when an employee has some experience but is still in the process of learning. It involves the leader providing guidance, feedback, and support while allowing the employee to take the lead. The leader should ask questions, provide feedback, and offer assistance when needed.

- Supporting is most appropriate when an employee is fairly experienced and able to work independently. It involves the leader providing encouragement and guidance while allowing the employee to take the lead. The leader should provide resources, challenge the employee to take on more responsibility, and offer assistance when needed.

- Delegating is an appropriate strategy when an employee is highly experienced and capable of handling the task without much guidance. It involves the leader assigning tasks to the employee and trusting that they will complete the task on their own. The leader should provide resources, set expectations, and offer support when needed.

Situational leadership also requires regular communication between the leader and team members. Leaders should use regular check-ins to assess progress and provide feedback. This will help ensure that everyone is on the same page and that any issues are addressed in a timely manner. By taking the time to understand the situation and the individuals involved, leaders can use situational leadership to create an environment where employees feel empowered and motivated.

Let’s look at two archetypes that I found were common, and the level of scoping and type of leadership they tended to need (at least at first; in theory, you should move from directing to delegating with each employee on each type of project at each level of scoping, until finally they’re all Super Directors and you win capitalism together).

The early career L1: some analysts come out of school ready to build recommendations for directors. But most require about six months of investment before they’re of much use in a fast-moving revenue-focused business. Take Jackson*, whom I hired straight out of college, and who demonstrated pretty significant coding ability in his interview.

Managing Jackson mostly required directing, which came down to four components:

-

Scope thoroughly: breaking tasks down into smaller chunks was essential to make them easy enough for Jackson to complete them. It also helped him understand what was expected of him and how he should go about it. It took a little bit of time to figure out what kind of “chunks” he was capable of tackling on his own. If I needed a Data Studio dashboard that would monitor certain metrics for instance, I would need to sketch out the dashboard and label what each component would show. But with that, Jackson was more than capable of connecting the right data and visualizing it satisfactorily. Stretching his abilities involved starting to leave the design component more ambiguous, for example explaining what a page of the dashboard should demonstrate, without enumerating each visual.

-

Set specific deadlines: these forced Jackson to take an approach that was appropriately thorough for the value of the task he was working on. For example, if a dashboard was something we’d only use once, I’d give it something like a 1-day deadline, which would force him to make quick connections and not worry to much about creating perfect visuals with, say, optimal color coding. Additionally, whenever work started piling up, I’d reinforce that it’s generally okay to miss deadlines as long as he was proactively letting me know as soon as it was possible a deadline could be missed. As a result, Jackson started managing upwards, telling me when new responsibilities could get in the way of his current deadlines.

-

Check in regularly: “directing” is high touch. All those deadlines don’t mean much if you’re not checking in once a week - and probably more - to assess progress and provide feedback, as well as give an explicit opportunity to ask questions - something new hires are sometimes reticent to do.

-

Provide resources: if there are any resources that Jackson needs to complete these tasks, make sure to provide them upfront. This could include online tutorials, access to databases, or especially examples of other similar work that was done well.

* Names changed, of course. I’ve hired a few Jacksons, in any case :)

The advanced L2: a strong L2 is light years (which are just as long, time-wise, as regular years) ahead of a new hire. If they started in the role as an L1, they’ve likely touched each part of the job a few times, and have seen others tackle thorny problems. They’re able to tackle easier projects independently, but will require support, coaching, and even directing for others. Take Jennifer, whom I hired as an L1 with industry experience and eventually promoted to L2.

Managing Jennifer required identifying which parts of a project required what level of scoping and leadership. For example, she had worked as a veritable data scientist, and her coding abilities were top level among the search marketing analysts. She could take a directive like “automate this model so that it executes without any intervention, and reports out results”, and run with it, needing only occasional answers or resources. However, finding a fast and MECE approach to a business problem was harder for her. To solve a problem like the landing page issue alluded to earlier, I would have needed to coach her heavily through step 1, breaking down the components of the landing page into discrete parts to analyze. Once the framework of analysis was set up, I could support her as she explored each one, encouraging her to move on to the next area before she spent too long getting an unnecessarily perfect answer.

The main takeaway from each of these examples is that for every task and person working on it, a different level of leadership is required.

3. Be your own coach

Step 1: watch Ted Lasso

Step 2: get a job as a data analyst manager at a fortune 100 company

Step 3: ???

Step 4: profit

You don’t need to be a manager to be a coach. Asking yourself the right questions can squeeze better results out of your own projects. Here are some I’ve relied on over the years; these work on yourself and others.

- Define the problem

- What other angles can you think of?

- What’s not clear yet for you?

- What’s one more possibility?

- What else?

- Solve the problem

- What resources do you need to help you decide?

- What seems to be the main obstacle?

- What action will you take?

- Integrate what you’ve learned

- What do you think will be the end result?

- What will you take away from this?

For example, an analyst might come to me saying they’re stuck on how to curate images for an imagery test. If I were short on time or there were a lot of questions to get through, perhaps I’d just give them the answer. But if we had the time, coaching them with these questions could allow them to solve the problem on their own; and their approach could be something I hadn’t thought of.

So, you’ve made it to the bottom of this article. What will you take away from this?